Tuesday, May 24, 2005

Two Dicks and an old Dog: Time magazine's top 100 movies

Time magazine film critics Richard Schickel and Richard Corliss have compiled a list of their top hundred films. This strikes me as a good way to open a wider cultural discussion about cinema, its cultural importance, and its status as a popular art form, as long as no one takes it too seriously. So watch closely, gentle reader, as I flagrantly violate this rule.

Back in 2003, I started my blog with a list of top ten films, secure in the knowledge that I could cook up a perfectly decent post on any of them whenever I was stuck for a topic. But as much as I enjoy talking about cinema, I don't think I'm sufficiently acquainted with it to produce anything like a top hundred list, and even if I were, I'm not sure it would necessarily be worth the bother. Long lists imply comprehensiveness, something which is impossible in an art form as varied as the cinema, and I'd almost certainly forget something important, or include something I would later regret.

For example, I look back on my own inclusion of Apocalypse Now Redux with embarrassment. At the time, I noted that the "redux" verions offered something that Coppola's original didn't: Instead of condemning war out of hand as futile and absurd (what else is new?), Apocalypse Now Redux offered a broader discussion of how wars should be fought, and a narrower view of Vietnam as a specific war (instead of a template for any sort of armed conflict). I still think Redux as a great movie, but I'm not sure it belongs in such an exalted pantheon. Eventually I'll transfer that honor to Peckinpah's Wild Bunch, which very nearly made my top ten in the first place (though it didn't rate so much as a peep from Schickel and Corliss).

When faced with a task of this sort, one must consider the politics of list-making. I took care to include D.W. Griffith's Birth of a Nation on my ten-greatest list, partly because it turned cinema from an afternoon diversion to a full evening's entertainment, partly because it demonstrated that the virtuosic technique of Griffith's short films could be sustained in a three-hour feature to even greater effect. The film's impact on audiences is as incontestible as its effect on world cinema. Still, when you include a film that praises the Ku Klux Klan in a list of great movies, you'd better prepare yourself for the political fallout: The only reason I didn't experience any (at the time), was that I was too new on the blogosphere for anyone to care.

The Time critics decorously avoid Griffith, along with most of the silent era; the earliest film on their list is Keaton's 1924 Sherlock, Jr. (also on my top ten). But they don't shy away from Nazi propagandist Leni Riefenstahl, whose two documentaries for the Party strike me as the decadent last gasp of German Expressionism. Her Triumph of the Will may be better known -- and in its twisted way, it might be a better film. But Schickel and Corliss have chosen her less overtly political four-hour chronicle of the Berlin Olympics, Olympia, a film which inspired critics to coin the phrase "body fascism." (Godard once quipped that the history of cinema consisted of men watching girls, but Olympia memorably reversed that gender dynamic; it may be the most "scopophilic" movie ever made.) Although I think the term "body fascism" is often misused, it seems perfectly appropriate in this case; Riefenstahl's anonymous and aestheticized Aryan bodies exist, like the film itself, to glorify the Nazi state. Within a few years, many of Riefenstahl's perfect Nazi bodies would lie dying on the fields of Russia and Western Europe, and in the deserts of Africa.

The list features four westerns, only one of which -- John Ford's The Searchers -- dates from the genre's golden age, and is a late, cynical arrival. (I suppose we should be grateful for a glance in Ford's direction, since most classic westerns are currently out of critical favor.) Of the three remaining, two are late-'60s spaghetti westerns from Sergio Leone -- you've probably guessed which ones gentle reader, because they're the same ones everyone else cites: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly and the severely overrated Once Upon a Time in the West. The most recent is Clint Eastwood's Unforgiven, a dim, angry, claustrophobic movie with an all-star cast. It's not as lively as The Outlaw Josey Wales (still Eastwood's best movie), but at least it's ready to make the claim that the myth of a Wild West is responsible for Everything That Is Wrong With America. It's pretty clear that Schickel and Corliss like their westerns neurotic, self-critical, and overly stylized: After all, if Red River isn't dark enough for these guys, what chance would a comparatively upbeat film like Stagecoach have?

Some of the critics' choices are bizarre: For the obligatory Jean Renoir film, they sidestep Grand Illusion and Rules of the Game to exalt a minor socialist-agitprop relic, Le Crime de M. Lange. The Coen brothers are represented by the facile Miller's Crossing instead of their majestically forlorn Fargo. Robert Bresson gets a mention for the sordid Mouchette (a film one would rather recall than see), rather than Pickpocket, Diary of a Country Priest or Au Hasard Balthasar. Ernst Lubitsch is honored for The Shop Around the Corner, not Trouble in Paradise.

Martin Scorsese, the Elvis Costello of moviedom, gets three films on the list -- Taxi Driver, Raging Bull, and Goodfellas. I'm not certain he's worth so much fuss, especially when the films of John Huston go unmentioned, but it's easy to see how he draws their praise. Scorsese doesn't make movies, he remakes them: His filmmaking is always, impeccably derivative. The nightclub scene in Goodfellas, with its long tracking shot, is justly praised -- but the nightclub scenes in Howard Hawks's Scarface and Raoul Walsh's Roaring Twenties which inspired it are no less impressive or fluid, and have the added advantage of originality. Of course, Scarface is a pre-Code gangster melodrama, with all the creaky sincerity of a story ripped from newspaper headlines (and even a fascist subtext in one scene), and Roaring Twenties epitomizes the classic Hollywood style, while Goodfellas is a gritty homage to gangster movies, filtered through memory and a 1970s auteurist sensibility.

Ultimately, Scorsese's encyclopedic knowledge of film history and ability to reproduce shots and scenes from earlier films with uncanny accuracy make him a perfect director for film critics. They can see in his oeuvre a condensed history of cinema, rewritten and "corrected" (to borrow a term from Robert Ray) to suit their own expectations and tastes. Quentin Tarantino, whose Pulp Fiction adorns the list, offers the same kind of secondhand pleasure, though his sources are more deliberately lowbrow.

The Time critics display at least one bias that, on second glance, might qualify as outright prejudice: Schickel and Corliss prefer classic American films when they're helmed by foreign-born directors, believing (as Richard Corliss claims about William Wyler's Dodsworth) that these directors "brought an outsider's vision, as fascinated as it was skeptical, to American social issues." I suppose one can note with some pride that only an American, native-born or naturalized, would consider a outsider's vision of our culture somehow more authoritative than an insider's, that we believe our culture resilient enough not to handle it with kid gloves or insist that foreigners seek our approval before they speak of us. The French certainly don't seem to feel that way about their culture: In the early '80s, when American director Sam Fuller made a thriller about unemployed youth (Voleurs de la nuit), these critics told him in no uncertain terms to stick to his own kind. You don't get bonus points for being an outsider in France.

I don't go as far as the French, but all the same, I can't fathom why Billy Wilder, with his fashionable Continental ennui, should have greater insight into American manners and mores than the straightforward Henry King, or why Edgar G. Ulmer would be a more reliable observer of our society than William Wellman. For that matter, one wonders why Corliss attributes the close observation in the film Dodsworth to its director Wyler, when Minnesota-born Sinclair Lewis, who wrote the novel on which the film was based, had won a Nobel Prize six years earlier for recording the social fluctuations of American life. (Admittedly, Lewis's fascination with America was tinged with disdain and repugnance, especially when he dealt with the middle class, but the man certainly knew his territory.)

Perhaps this predilection for the exotic might explain the absence of Wellman and Huston, the gross underrepresentation of Howard Hawks and John Ford, and the near-erasure of the American western -- and not just on this particular list. It would seem as though we don't pay attention to this "white-bread" cinema, because we already know (or think we know) what it will say about us. The Time critics didn't shy away entirely from popular success: They chose to honor E.T., Star Wars and King Kong, Disney's Pinocchio and, somewhat less fortuitously, Pixar's recent Finding Nemo. However, in order to validate Disney and Pixar, our dazzling duo had to invoke Soviet director Sergei Eisenstein, just to prove that they didn't pick cartoons just because uninformed viewers happen to like them. (It's ironic that animated cartoons -- which of all forms of filmmaking make greatest and most painstaking use of traditional media -- are so widely despised among those who consider cinema high art.)

I can't object to the idea of making this sort of list, though on some level I hope that Time magazine has better things to do than congratulate themselves for having two film critics on staff. (Schickel rates as more than a mere critic: His recent reconstruction of Samuel Fuller's The Big Red One establishes him as a craftsman in his own right.) I'm also glad that the critics chose to plug a few little-known films that deserve a wider audience (Leolo), and classic movies currently unavailable on DVD (Baby Face -- which I've only seen in its truncated version -- and shockingly enough, the original King Kong). I should also applaud the critics' devotion to foreign films: I'm not convinced many of them are much better than American movies, but you can't know that until you actually see them, and relatively few Americans do. One imagines these films are so difficult to find in part because cinephiles want to preserve their mystique.

NPR film critic Kenneth Tynan recently published Never Coming to a Theater Near You, a book of reviews devoted to neglected or little-known movies, which should offer plenty of sugggested viewing for a strange and adventurous Friday night. At any rate, Time magazine has provided as good an opportunity as any to look up a few films that you may not have seen or heard of before -- and gripe about inevitable oversights.

Time magazine film critics Richard Schickel and Richard Corliss have compiled a list of their top hundred films. This strikes me as a good way to open a wider cultural discussion about cinema, its cultural importance, and its status as a popular art form, as long as no one takes it too seriously. So watch closely, gentle reader, as I flagrantly violate this rule.

Back in 2003, I started my blog with a list of top ten films, secure in the knowledge that I could cook up a perfectly decent post on any of them whenever I was stuck for a topic. But as much as I enjoy talking about cinema, I don't think I'm sufficiently acquainted with it to produce anything like a top hundred list, and even if I were, I'm not sure it would necessarily be worth the bother. Long lists imply comprehensiveness, something which is impossible in an art form as varied as the cinema, and I'd almost certainly forget something important, or include something I would later regret.

For example, I look back on my own inclusion of Apocalypse Now Redux with embarrassment. At the time, I noted that the "redux" verions offered something that Coppola's original didn't: Instead of condemning war out of hand as futile and absurd (what else is new?), Apocalypse Now Redux offered a broader discussion of how wars should be fought, and a narrower view of Vietnam as a specific war (instead of a template for any sort of armed conflict). I still think Redux as a great movie, but I'm not sure it belongs in such an exalted pantheon. Eventually I'll transfer that honor to Peckinpah's Wild Bunch, which very nearly made my top ten in the first place (though it didn't rate so much as a peep from Schickel and Corliss).

When faced with a task of this sort, one must consider the politics of list-making. I took care to include D.W. Griffith's Birth of a Nation on my ten-greatest list, partly because it turned cinema from an afternoon diversion to a full evening's entertainment, partly because it demonstrated that the virtuosic technique of Griffith's short films could be sustained in a three-hour feature to even greater effect. The film's impact on audiences is as incontestible as its effect on world cinema. Still, when you include a film that praises the Ku Klux Klan in a list of great movies, you'd better prepare yourself for the political fallout: The only reason I didn't experience any (at the time), was that I was too new on the blogosphere for anyone to care.

The Time critics decorously avoid Griffith, along with most of the silent era; the earliest film on their list is Keaton's 1924 Sherlock, Jr. (also on my top ten). But they don't shy away from Nazi propagandist Leni Riefenstahl, whose two documentaries for the Party strike me as the decadent last gasp of German Expressionism. Her Triumph of the Will may be better known -- and in its twisted way, it might be a better film. But Schickel and Corliss have chosen her less overtly political four-hour chronicle of the Berlin Olympics, Olympia, a film which inspired critics to coin the phrase "body fascism." (Godard once quipped that the history of cinema consisted of men watching girls, but Olympia memorably reversed that gender dynamic; it may be the most "scopophilic" movie ever made.) Although I think the term "body fascism" is often misused, it seems perfectly appropriate in this case; Riefenstahl's anonymous and aestheticized Aryan bodies exist, like the film itself, to glorify the Nazi state. Within a few years, many of Riefenstahl's perfect Nazi bodies would lie dying on the fields of Russia and Western Europe, and in the deserts of Africa.

The list features four westerns, only one of which -- John Ford's The Searchers -- dates from the genre's golden age, and is a late, cynical arrival. (I suppose we should be grateful for a glance in Ford's direction, since most classic westerns are currently out of critical favor.) Of the three remaining, two are late-'60s spaghetti westerns from Sergio Leone -- you've probably guessed which ones gentle reader, because they're the same ones everyone else cites: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly and the severely overrated Once Upon a Time in the West. The most recent is Clint Eastwood's Unforgiven, a dim, angry, claustrophobic movie with an all-star cast. It's not as lively as The Outlaw Josey Wales (still Eastwood's best movie), but at least it's ready to make the claim that the myth of a Wild West is responsible for Everything That Is Wrong With America. It's pretty clear that Schickel and Corliss like their westerns neurotic, self-critical, and overly stylized: After all, if Red River isn't dark enough for these guys, what chance would a comparatively upbeat film like Stagecoach have?

Some of the critics' choices are bizarre: For the obligatory Jean Renoir film, they sidestep Grand Illusion and Rules of the Game to exalt a minor socialist-agitprop relic, Le Crime de M. Lange. The Coen brothers are represented by the facile Miller's Crossing instead of their majestically forlorn Fargo. Robert Bresson gets a mention for the sordid Mouchette (a film one would rather recall than see), rather than Pickpocket, Diary of a Country Priest or Au Hasard Balthasar. Ernst Lubitsch is honored for The Shop Around the Corner, not Trouble in Paradise.

Martin Scorsese, the Elvis Costello of moviedom, gets three films on the list -- Taxi Driver, Raging Bull, and Goodfellas. I'm not certain he's worth so much fuss, especially when the films of John Huston go unmentioned, but it's easy to see how he draws their praise. Scorsese doesn't make movies, he remakes them: His filmmaking is always, impeccably derivative. The nightclub scene in Goodfellas, with its long tracking shot, is justly praised -- but the nightclub scenes in Howard Hawks's Scarface and Raoul Walsh's Roaring Twenties which inspired it are no less impressive or fluid, and have the added advantage of originality. Of course, Scarface is a pre-Code gangster melodrama, with all the creaky sincerity of a story ripped from newspaper headlines (and even a fascist subtext in one scene), and Roaring Twenties epitomizes the classic Hollywood style, while Goodfellas is a gritty homage to gangster movies, filtered through memory and a 1970s auteurist sensibility.

Ultimately, Scorsese's encyclopedic knowledge of film history and ability to reproduce shots and scenes from earlier films with uncanny accuracy make him a perfect director for film critics. They can see in his oeuvre a condensed history of cinema, rewritten and "corrected" (to borrow a term from Robert Ray) to suit their own expectations and tastes. Quentin Tarantino, whose Pulp Fiction adorns the list, offers the same kind of secondhand pleasure, though his sources are more deliberately lowbrow.

The Time critics display at least one bias that, on second glance, might qualify as outright prejudice: Schickel and Corliss prefer classic American films when they're helmed by foreign-born directors, believing (as Richard Corliss claims about William Wyler's Dodsworth) that these directors "brought an outsider's vision, as fascinated as it was skeptical, to American social issues." I suppose one can note with some pride that only an American, native-born or naturalized, would consider a outsider's vision of our culture somehow more authoritative than an insider's, that we believe our culture resilient enough not to handle it with kid gloves or insist that foreigners seek our approval before they speak of us. The French certainly don't seem to feel that way about their culture: In the early '80s, when American director Sam Fuller made a thriller about unemployed youth (Voleurs de la nuit), these critics told him in no uncertain terms to stick to his own kind. You don't get bonus points for being an outsider in France.

I don't go as far as the French, but all the same, I can't fathom why Billy Wilder, with his fashionable Continental ennui, should have greater insight into American manners and mores than the straightforward Henry King, or why Edgar G. Ulmer would be a more reliable observer of our society than William Wellman. For that matter, one wonders why Corliss attributes the close observation in the film Dodsworth to its director Wyler, when Minnesota-born Sinclair Lewis, who wrote the novel on which the film was based, had won a Nobel Prize six years earlier for recording the social fluctuations of American life. (Admittedly, Lewis's fascination with America was tinged with disdain and repugnance, especially when he dealt with the middle class, but the man certainly knew his territory.)

Perhaps this predilection for the exotic might explain the absence of Wellman and Huston, the gross underrepresentation of Howard Hawks and John Ford, and the near-erasure of the American western -- and not just on this particular list. It would seem as though we don't pay attention to this "white-bread" cinema, because we already know (or think we know) what it will say about us. The Time critics didn't shy away entirely from popular success: They chose to honor E.T., Star Wars and King Kong, Disney's Pinocchio and, somewhat less fortuitously, Pixar's recent Finding Nemo. However, in order to validate Disney and Pixar, our dazzling duo had to invoke Soviet director Sergei Eisenstein, just to prove that they didn't pick cartoons just because uninformed viewers happen to like them. (It's ironic that animated cartoons -- which of all forms of filmmaking make greatest and most painstaking use of traditional media -- are so widely despised among those who consider cinema high art.)

I can't object to the idea of making this sort of list, though on some level I hope that Time magazine has better things to do than congratulate themselves for having two film critics on staff. (Schickel rates as more than a mere critic: His recent reconstruction of Samuel Fuller's The Big Red One establishes him as a craftsman in his own right.) I'm also glad that the critics chose to plug a few little-known films that deserve a wider audience (Leolo), and classic movies currently unavailable on DVD (Baby Face -- which I've only seen in its truncated version -- and shockingly enough, the original King Kong). I should also applaud the critics' devotion to foreign films: I'm not convinced many of them are much better than American movies, but you can't know that until you actually see them, and relatively few Americans do. One imagines these films are so difficult to find in part because cinephiles want to preserve their mystique.

NPR film critic Kenneth Tynan recently published Never Coming to a Theater Near You, a book of reviews devoted to neglected or little-known movies, which should offer plenty of sugggested viewing for a strange and adventurous Friday night. At any rate, Time magazine has provided as good an opportunity as any to look up a few films that you may not have seen or heard of before -- and gripe about inevitable oversights.

Sunday, May 22, 2005

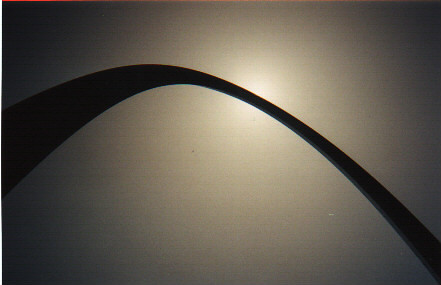

Photo of the Week: Gateway Arch, 1992

I've wanted to do more travel writing, and the onset of summer seems as good a time as any to start. Most of my favorite photos, the ones I'll post on this blog, involve seldom-seen corners of the United States. This one is an exception: I took it at midday, near the base of the Gateway Arch in St. Louis, Missouri. Since I live in Charlottesville, Virginia, home of our nation's third president, I suppose I should take pride in its official name: Jefferson National Expansion Memorial. Truth is, no one really calls it that. People refer to this structure, quite simply, as "The Arch."

This steel rainbow looming some two hundred meters over the St. Louis riverfront was built to commemorate America's westward expansion. That said, it isn't exactly a historical monument in any sense of the term. It's far too abstract for that. "Anti-historical" would describe the Arch more aptly, since it manages to obliterate the history it touches just as surely as antimatter wipes out matter. To find the real story of the American West -- or at least some fragment of it -- you have to look away from the cities, off the beaten path.

At the Arch, Disneyland meets PBS. The memorial has a theme-park ambience (along with theme-park crowds), while maintaining the slightly stuffy tone reserved for serious education. It is breathtaking and dull, all at once. A jolting tram ride -- in tiny, four-person cylinders that bear an alarming resemblance to tin cans -- will hoist you to the apex of the Arch, where you can look at all the other skyscrapers in downtown St. Louis. Ironically for a monument dedicated to the West, the Arch's best views lie to the East, with a vista of the mile-wide Mississippi River and the Illinois suburbs.

A history museum crouches bunker-like at the base. It has a stuffed buffalo and an authentic Indian teepee, and dozens of text displays to let you know just how important they are. At least it's cool and dim down there, and would be a welcome break on a hot summer day but for the noisy throngs of people waiting for something they'd rather do instead. Perhaps some of them are waiting for a movie, since the memorial also contains two cinemas. One offers a half-hour film on the Arch's construction, and another shows IMAX documentaries on a screen slightly smaller than the norm (it's only four stories tall; the average is closer to six). The courthouse where the Dred Scott case was first tried is a mere block from the Arch and the museum, but relatively few people bother with it. Unlike the rest of the complex, it's really historic -- and the Arch obliterates any history it touches.

Instead, the Arch is a testament to what some people forty years ago believed the future would entail. Architect Eero Saarinen, who also designed the TWA terminal at Dulles International Airport, was the last of those exuberant visionaries who could transform a simple airline concourse into a temple of the human spirit, all with flowing steel and concrete. But alas, Saarinen's supple, streamlined world of tomorrow never materialized: If anything, the objects in our lives, from suburban megastores to aerodynamically nightmarish SUVs, have grown more blocky and boxlike over the decades.

In our world of mostly straight horizontal and vertical lines, the single, aesthetically dominating curve of the Arch feels not only out of place, but out of time. And with no ground in the historic past, and no connection to our present or foreseeable future, the Arch simply stands beside the river, celebrating nothing but itself. In this respect, its narcissism is perfect -- but then again, so is its charisma.

The Arch wasn't the last gasp of gargantuan triumphialism in America, but it was close. Only the late, lamented World Trade Center managed to surpass The Arch in size or scale, though the twin towers were so graceless that they achieved iconic status only after their destruction. Today's memorials -- like the ones in our nation's capital to FDR, World War II, and the Korean and Vietnam wars -- are sordid, low-slung affairs, burrowing into the ground rather than towering over it. (In the case of the Korean and Vietnam memorials, the quality is not inappropriate.) Perhaps the proposed Freedom Tower on the site of the old World Trade Center will reverse the trend, assuming it is ever built. On the other hand, perhaps that memorial will become such a blight on the New York City skyline that no one will ever build another.

In a way, though, today's tiny monuments seem fitting and just: After all, the human spirit isn't what it used to be, and it could be argued that neither is America. Yet I can't help thinking that the Arch, however devoid of purpose it may be, deserves to draw its crowds, if only because its presence reminds us that once, not so long ago, Americans had the gumption and the gall to build it.

I've wanted to do more travel writing, and the onset of summer seems as good a time as any to start. Most of my favorite photos, the ones I'll post on this blog, involve seldom-seen corners of the United States. This one is an exception: I took it at midday, near the base of the Gateway Arch in St. Louis, Missouri. Since I live in Charlottesville, Virginia, home of our nation's third president, I suppose I should take pride in its official name: Jefferson National Expansion Memorial. Truth is, no one really calls it that. People refer to this structure, quite simply, as "The Arch."

This steel rainbow looming some two hundred meters over the St. Louis riverfront was built to commemorate America's westward expansion. That said, it isn't exactly a historical monument in any sense of the term. It's far too abstract for that. "Anti-historical" would describe the Arch more aptly, since it manages to obliterate the history it touches just as surely as antimatter wipes out matter. To find the real story of the American West -- or at least some fragment of it -- you have to look away from the cities, off the beaten path.

At the Arch, Disneyland meets PBS. The memorial has a theme-park ambience (along with theme-park crowds), while maintaining the slightly stuffy tone reserved for serious education. It is breathtaking and dull, all at once. A jolting tram ride -- in tiny, four-person cylinders that bear an alarming resemblance to tin cans -- will hoist you to the apex of the Arch, where you can look at all the other skyscrapers in downtown St. Louis. Ironically for a monument dedicated to the West, the Arch's best views lie to the East, with a vista of the mile-wide Mississippi River and the Illinois suburbs.

A history museum crouches bunker-like at the base. It has a stuffed buffalo and an authentic Indian teepee, and dozens of text displays to let you know just how important they are. At least it's cool and dim down there, and would be a welcome break on a hot summer day but for the noisy throngs of people waiting for something they'd rather do instead. Perhaps some of them are waiting for a movie, since the memorial also contains two cinemas. One offers a half-hour film on the Arch's construction, and another shows IMAX documentaries on a screen slightly smaller than the norm (it's only four stories tall; the average is closer to six). The courthouse where the Dred Scott case was first tried is a mere block from the Arch and the museum, but relatively few people bother with it. Unlike the rest of the complex, it's really historic -- and the Arch obliterates any history it touches.

Instead, the Arch is a testament to what some people forty years ago believed the future would entail. Architect Eero Saarinen, who also designed the TWA terminal at Dulles International Airport, was the last of those exuberant visionaries who could transform a simple airline concourse into a temple of the human spirit, all with flowing steel and concrete. But alas, Saarinen's supple, streamlined world of tomorrow never materialized: If anything, the objects in our lives, from suburban megastores to aerodynamically nightmarish SUVs, have grown more blocky and boxlike over the decades.

In our world of mostly straight horizontal and vertical lines, the single, aesthetically dominating curve of the Arch feels not only out of place, but out of time. And with no ground in the historic past, and no connection to our present or foreseeable future, the Arch simply stands beside the river, celebrating nothing but itself. In this respect, its narcissism is perfect -- but then again, so is its charisma.

The Arch wasn't the last gasp of gargantuan triumphialism in America, but it was close. Only the late, lamented World Trade Center managed to surpass The Arch in size or scale, though the twin towers were so graceless that they achieved iconic status only after their destruction. Today's memorials -- like the ones in our nation's capital to FDR, World War II, and the Korean and Vietnam wars -- are sordid, low-slung affairs, burrowing into the ground rather than towering over it. (In the case of the Korean and Vietnam memorials, the quality is not inappropriate.) Perhaps the proposed Freedom Tower on the site of the old World Trade Center will reverse the trend, assuming it is ever built. On the other hand, perhaps that memorial will become such a blight on the New York City skyline that no one will ever build another.

In a way, though, today's tiny monuments seem fitting and just: After all, the human spirit isn't what it used to be, and it could be argued that neither is America. Yet I can't help thinking that the Arch, however devoid of purpose it may be, deserves to draw its crowds, if only because its presence reminds us that once, not so long ago, Americans had the gumption and the gall to build it.

Subscribe to Comments [Atom]