Thursday, June 02, 2005

Cinderella Man and the amazing Paul Giamatti

Let us now praise Paul Giamatti, probably the hardest-working actor in film and certainly one of the best. His performance in Sideways was the primary reason for that film's success, even though it wasn't up to his brilliant work in American Splendor the year before. Between these performances, he takes character roles in mainstream movies, and frequently walks away with them.

Which brings us to Ron Howard's Cinderella Man, sporting the worst title possible for a boxing picture. This Depression-era "mellerdrammer" tells the story of legendary prizefighter Jim J. Braddock -- though with such a gender-confused title, you expect something along the lines of Jim J. Bullock instead. Alas, instead of drag queens and sitcom shenanigans, we get Russell Crowe, trying to affect an American accent and slur his speech like a real boxer might. In this film Crowe looks rather like Sylvester Stallone, only without the ambition or intelligence.

Prim and demure Renee Zellweger -- the new millennium's answer to the Angel of the Household -- is about as lovely as anyone on a steady diet of green persimmons could be. As Mrs. Jim J. Braddock, she provides the film with the necessary domestic drama: She worries about Jim, she worries about her family, she worries about Russell Crowe's hand, about the boxing commission. Mostly she worries about how to pay the bills. (With a figure like hers, I'd suggest she dye her hair and get work as a chorus girl, like the smart, perky dames of pre-code Hollywood. But I suppose that would soil her somehow.)

Ron Howard is desperate to make this picture "respectable" -- a declawed housecat, instead of a raging bull. He can't change the fact that boxing involves two people in a ring trying to pound the crap out of each other, but he can softpedal the brutality a bit with home-and-hearth rhetoric and a generous dose of classic-Hollywood formula. You see, Bullock -- er, Braddock -- gets in the ring because it's the only way he can put food on the table. Meanwhile, Braddock's opponent Max Baer (Craig Bierko, more convincing in the ring than Crowe) engages in rampant womanizing, braggadocio, and general bad behavior: He even makes a nasty pass at Braddock's wife, something the real-life Max Baer probably wouldn't have done. Will Braddock's clean livin' triumph over Baer's cruelty and decadence? Is Hollywood in California?

Only a real pro could keep this movie on its feet -- and this is where Paul Giamatti comes back in. He plays Braddock's manager, unluckily named "Joe Gould" (no relation to Joseph Mitchell's "odd and penniless and unemployable little man" with a big secret). The "fight manager" has the juiciest role in any boxing movie, and Giamatti gives this shopworn part a surprisingly dapper spin. He's slightly pudgy and dandified, the perfect liaison to a skeptical press, as well as to a hostile boxing commission, and when we finally peer behind his character's facade, it's the only genuinely moving scene in the film. Best of all, Giamatti engages the other characters and the audience with patter so rich and witty that, as one character remarks, "they oughta put his mouth in a circus." Russell Crowe may play the "Cinderella Man," but Giamatti walks off with the glass slipper.

I should point out the film's only notable stylistic feature: During the early scenes, as the Braddock household sinks into debt and despair, Howard uses jittery handheld cameras and dim, naturalistic lighting to capture the grit and desperation of those early Depression years. Those verite touches would be more effective, of course, if Howard had mere actors in front of the camera instead of stars (as was also the case for his crowd-pleasing Apollo 13). Still, that jittery camera offers a welcome respite from the "period gloss" and imitation classic-Hollywood style that sink the rest of the film.

Cinderella Man is always eager to please: It wants to be a contender. But despite Giamatti's flawless character turn, this movie is just a flabby old has-been, with sloppy footwork, a glass jaw, and punches so slow you can see them a mile away. A real boxing movie, like Walter Hill's Undisputed,0 would knock poor Cinderella on the canvas faster than Tyson kayoed Spinks.

Let us now praise Paul Giamatti, probably the hardest-working actor in film and certainly one of the best. His performance in Sideways was the primary reason for that film's success, even though it wasn't up to his brilliant work in American Splendor the year before. Between these performances, he takes character roles in mainstream movies, and frequently walks away with them.

Which brings us to Ron Howard's Cinderella Man, sporting the worst title possible for a boxing picture. This Depression-era "mellerdrammer" tells the story of legendary prizefighter Jim J. Braddock -- though with such a gender-confused title, you expect something along the lines of Jim J. Bullock instead. Alas, instead of drag queens and sitcom shenanigans, we get Russell Crowe, trying to affect an American accent and slur his speech like a real boxer might. In this film Crowe looks rather like Sylvester Stallone, only without the ambition or intelligence.

Prim and demure Renee Zellweger -- the new millennium's answer to the Angel of the Household -- is about as lovely as anyone on a steady diet of green persimmons could be. As Mrs. Jim J. Braddock, she provides the film with the necessary domestic drama: She worries about Jim, she worries about her family, she worries about Russell Crowe's hand, about the boxing commission. Mostly she worries about how to pay the bills. (With a figure like hers, I'd suggest she dye her hair and get work as a chorus girl, like the smart, perky dames of pre-code Hollywood. But I suppose that would soil her somehow.)

Ron Howard is desperate to make this picture "respectable" -- a declawed housecat, instead of a raging bull. He can't change the fact that boxing involves two people in a ring trying to pound the crap out of each other, but he can softpedal the brutality a bit with home-and-hearth rhetoric and a generous dose of classic-Hollywood formula. You see, Bullock -- er, Braddock -- gets in the ring because it's the only way he can put food on the table. Meanwhile, Braddock's opponent Max Baer (Craig Bierko, more convincing in the ring than Crowe) engages in rampant womanizing, braggadocio, and general bad behavior: He even makes a nasty pass at Braddock's wife, something the real-life Max Baer probably wouldn't have done. Will Braddock's clean livin' triumph over Baer's cruelty and decadence? Is Hollywood in California?

Only a real pro could keep this movie on its feet -- and this is where Paul Giamatti comes back in. He plays Braddock's manager, unluckily named "Joe Gould" (no relation to Joseph Mitchell's "odd and penniless and unemployable little man" with a big secret). The "fight manager" has the juiciest role in any boxing movie, and Giamatti gives this shopworn part a surprisingly dapper spin. He's slightly pudgy and dandified, the perfect liaison to a skeptical press, as well as to a hostile boxing commission, and when we finally peer behind his character's facade, it's the only genuinely moving scene in the film. Best of all, Giamatti engages the other characters and the audience with patter so rich and witty that, as one character remarks, "they oughta put his mouth in a circus." Russell Crowe may play the "Cinderella Man," but Giamatti walks off with the glass slipper.

I should point out the film's only notable stylistic feature: During the early scenes, as the Braddock household sinks into debt and despair, Howard uses jittery handheld cameras and dim, naturalistic lighting to capture the grit and desperation of those early Depression years. Those verite touches would be more effective, of course, if Howard had mere actors in front of the camera instead of stars (as was also the case for his crowd-pleasing Apollo 13). Still, that jittery camera offers a welcome respite from the "period gloss" and imitation classic-Hollywood style that sink the rest of the film.

Cinderella Man is always eager to please: It wants to be a contender. But despite Giamatti's flawless character turn, this movie is just a flabby old has-been, with sloppy footwork, a glass jaw, and punches so slow you can see them a mile away. A real boxing movie, like Walter Hill's Undisputed,0 would knock poor Cinderella on the canvas faster than Tyson kayoed Spinks.

Sunday, May 29, 2005

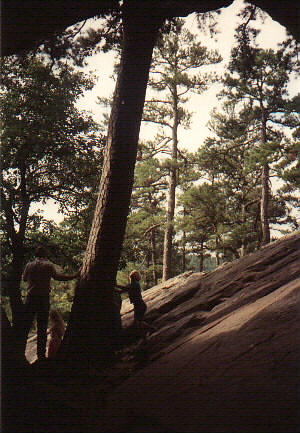

Photo of the Week: Robbers Cave State Park, Wilburton OK, 1990

"Tim," a friend tells me, "you always spend your vacations at the ass ends of creation."

It's true, more often than not. When I go on holiday, I'm more likely to visit rural Ohio than New York City, and one of the best vacations I ever had was in the Nebraska Sandhills. I don't go to these places because I want to "get away from it all." For me, these places are where "it" is -- whether "it" happens to be a beautiful vista, an unforgettable story, or simply a part of America that you never see on the evening news.

This photo was taken on the western end of the low-lying Ouachita mountains, where Charles Portis set his novel True Grit. (You'll notice that it looks nothing like the movie.) Robbers Cave State Park is a mid-sized "resort park" strung out along a state highway. Like most of its ilk, it lacks a real backcountry area, but it does have a campground, a small lodge with cabins, a nature center, three fishing lakes, and several short trails.

In case you're wondering where the cave is, I'm standing in it. (It's a rock shelter, not a cave proper.) At nine in the morning the light is still good: In another hour, my photos will start to look slightly bleached, like the country itself. This, you see, is where the prairie begins, the land of almost enough rain.

The cave got its name back when Oklahoma was merely "Indian Territory," and the only law in the region was the court of "hanging judge" Isaac Parker, in far-off Fort Smith, Arkansas. The entrance lies at the top of a high, rocky hill, the sort of boulder jumble you can see in a thousand B westerns. It's the perfect setting for a shootout, or an ambush -- and local legends claim that it hosted more than its share of both.

Everyone from Belle Starr to Jesse James is said to have holed up here; Starr might actually have done it, since her home was a mere twenty miles away. Still, as a campsite the cave has one major shortcoming: No fresh water. Any siege was bound to be a short one, a fact that more than one unwary lawman might have counted on for a favorable outcome, once they ordered their quarry to surrender.

But the cave held a surprise for them: At the rear, or so the legend goes, was a secret passage to the bottom of the hill, where those lawmen rested their horses and kept ammunition and supplies. It was easy enough for a bandit to sneak through the passage, steal their goods and scare off their animals, all before they knew what was happening. Officers of the law would find themselves afoot and empty-handed, in the middle of what was then only spottily settled wilderness.

That secret passage no longer exists (if it ever did), and today, the only outlaws who frequent the cave are teenagers who spray graffiti on the walls. In daylight hours, rappellers and climbers scramble around and over the rocks, while children, like the one in my photo, play cowboys-and-Indians in the shade.

Granted, there's not much left of the Old-West mystique in little Robbers Cave anymore. But if you look at it from the inside out, it's still kind of pretty, isn't it?

"Tim," a friend tells me, "you always spend your vacations at the ass ends of creation."

It's true, more often than not. When I go on holiday, I'm more likely to visit rural Ohio than New York City, and one of the best vacations I ever had was in the Nebraska Sandhills. I don't go to these places because I want to "get away from it all." For me, these places are where "it" is -- whether "it" happens to be a beautiful vista, an unforgettable story, or simply a part of America that you never see on the evening news.

This photo was taken on the western end of the low-lying Ouachita mountains, where Charles Portis set his novel True Grit. (You'll notice that it looks nothing like the movie.) Robbers Cave State Park is a mid-sized "resort park" strung out along a state highway. Like most of its ilk, it lacks a real backcountry area, but it does have a campground, a small lodge with cabins, a nature center, three fishing lakes, and several short trails.

In case you're wondering where the cave is, I'm standing in it. (It's a rock shelter, not a cave proper.) At nine in the morning the light is still good: In another hour, my photos will start to look slightly bleached, like the country itself. This, you see, is where the prairie begins, the land of almost enough rain.

The cave got its name back when Oklahoma was merely "Indian Territory," and the only law in the region was the court of "hanging judge" Isaac Parker, in far-off Fort Smith, Arkansas. The entrance lies at the top of a high, rocky hill, the sort of boulder jumble you can see in a thousand B westerns. It's the perfect setting for a shootout, or an ambush -- and local legends claim that it hosted more than its share of both.

Everyone from Belle Starr to Jesse James is said to have holed up here; Starr might actually have done it, since her home was a mere twenty miles away. Still, as a campsite the cave has one major shortcoming: No fresh water. Any siege was bound to be a short one, a fact that more than one unwary lawman might have counted on for a favorable outcome, once they ordered their quarry to surrender.

But the cave held a surprise for them: At the rear, or so the legend goes, was a secret passage to the bottom of the hill, where those lawmen rested their horses and kept ammunition and supplies. It was easy enough for a bandit to sneak through the passage, steal their goods and scare off their animals, all before they knew what was happening. Officers of the law would find themselves afoot and empty-handed, in the middle of what was then only spottily settled wilderness.

That secret passage no longer exists (if it ever did), and today, the only outlaws who frequent the cave are teenagers who spray graffiti on the walls. In daylight hours, rappellers and climbers scramble around and over the rocks, while children, like the one in my photo, play cowboys-and-Indians in the shade.

Granted, there's not much left of the Old-West mystique in little Robbers Cave anymore. But if you look at it from the inside out, it's still kind of pretty, isn't it?

Subscribe to Comments [Atom]